One can certainly hike the Congo Nile Trail without knowing a word of Kinyarwanda, which is the name of Rwandans’ language. (The name of the language is actually Ikinyarwanda, but the Europeans dropped the beginning “I.”) But, it’s clearly more fun to know a few words and phrases so that you can interact and converse a bit with the numerous people, especially kids, whom you will encounter on the trail and hear their squeals of laughter when you say just a few, even mispronounced, words to them.

Rwandans are so appreciative of any foreigner who attempts their complex language that they gush about how well that person speaks Ikinyarwanda (pronounced EE-Chin-Your-Gwanda, giving you a glimpse of how difficult the language can be). When I say just a few of the simplest of words in Ikinyarwanda (like the equivalent of “Good afternoon. How are you?”, I often hear people commenting to one another about how well I speak the language – which is so different from how Americans react to a foreigner struggling with English. So, don’t worry about pronunciation. If you even attempt a few Ikinyarwanda words on the Trail, you’ll have a much happier experience because the Trail is not only about hiking and fabulous scenery but also about the interesting Rwandans you will meet and greet along the way.

GREETINGS

A word about greetings: Rwandans use a special greeting for someone they meet for the first time or haven’t seen in a long time. It’s Muraho (pronounced mer-ah-ho.). To say goodbye to someone forever or for a long time, they say Murabeho (pronounced mer-a-bay-ho). I always say “Muraho” when I meet an elderly person for the first time. You should use this greeting when you first meet your hosts at your overnight accommodations. It’s never wrong to say it to strangers you meet along the trail, but you can also use the greetings for good morning, etc. below.

Good morning – Mwaramutse (Mwar-a-moot-say). It is used until noon. The response to Mwaramutse is “Mwaramutse neza” (pronounced nay-za).

Good afternoon – Mwiriwe (Meer-ee-way). Start using this greeting around noon. Then use it all the way through evening and night. The response to Mwiriwe is “Mwiriwe neza.”

How are you? – “Amakuru” (pronounced ah-mah-koo-roo), which literally means “News?” Sometimes you may hear “Amakuru yawe?,” literally meaning “Your news?” If you happen to see the news on TV, you will see the word “amakuru.”

I’m fine – “Ni meza.” (Pronounced nee may-za) is the response to “Amakuru.” It literally means “It’s good.”

Hi – When greeting children, Rwandans usaully use the following informal greeting, which is similar to saying, “What’s up” or “How are things?”: “Bite” (pronounced bee-tay). The child’s response is “Ni byiza.” (Pronounced nee-beeza), meaning “It’s good.”

Thank you – Murakoze (pronounced mer-a-ko-zay).

Thank you, too – Murakoze namwe. (Namwe is pronounced nahm-way). In the tiny shops along the trail, the shopkeeper will almost always say this after you say “thank you.”

Thank you very much – Murakoze cyane (pronounced mer-a-ko-zay chah-nay).

Thank you very much, too. Murakoze cyane namwe or just “Namwe.”

Where is a bathroom? – Umusarani iri he? When nature calls on the Trail, there is seldom a private place to retire to, as people are everywhere. Even when you don’t notice them, they are looking at you. When you ask for a bathroom/toilet, you are likely to be taken through a seemingly circuitous route to someone’s private outhouse, which will likely be a tiny enclosure with a hole in the ground. So, bring your own paper and, when you leave, give your host ijana (100 francs) for their hospitality and thank them by saying, “Murakoze cyane.” Interestingly, because it’s hot during the day and you will be sweating, even though you are drinking a lot of water, you won’t often feel the need to urinate.

MORE ADVANCED GREETINGS

Have a good day –

Umunsi mwiza (pronounced oo-moon-see mwee-zah).

It literally means “Good day.”

Used as in English, when you are leaving someone. On the Trail, you can say this when leaving

your host in the morning, when leaving a shop or when leaving after having

engaged in a short conversation with someone you meet on the Trail. They will usually respond, “Umunsi mwiza

namwe” or simply “Namwe,” which basically means “You, too.”

Have a good work day – Akazi Keza (pronounced ah-kah-zee kay-za). It literally means “Good work.” When you see someone working in a field on a farm or going to or engaging in any kind of work, you can use this greeting. I love this greeting. People say it every morning to me as I go to work, and I say it anytime I see anyone working.

Be strong – Komera. The response is usually “Komera meza.” (pronounced Ko-mare-ah-may-za).

Peace – Amahoro. The response is “Amahoro meza.”

Good evening – Umugorobo mwiza (pronounced oo-moo-gor-oh-ba-mwee-zah). You can use this in place of Mwiriwe in the evening if you like, but don’t have to, as it’s fine to say Mwiriwe all evening.

Good night – Ijoro rwiza (pronounced ee-jor-oh-gee-za). Say this, as you would in English, when you are leaving to go home or to bed.

Good night, when leaving someone in the evening or at night – Muramuke (pronounced wither moo-rah-moo-kay OR moo-rah-moo-chay.

Goodbye – There are many ways to say goodbye depending on the time of day and how long it will be before you see the person again. For a permanent or long-time goodbye (e.g., leaving your host in the morning), say “Murabeho” (pronounced moo-rah-bay-ho).

HELPFUL WORDS TO KNOW

Yego – yes. It rhymes with Lego. Yego is often used as a response to any greeting, or the response to your response to a greeting. Rwandans like to have the last word in any conversation, and the last word is usually “Yego” and, when used this way, generally means “Good” or “I’ve heard you.” It’s a nice way of ending a conversation.

E.g. Person 1: Mwiriwe. (Good afternoon)

Person 2: Mwiriwe neza. (Good afternoon)

Person 1: Amakuru?

(How are you?)

Person 2: Ni

meza. Yawe? (I’m fine. And, you?”)

Person 1: Nanjye ni meza. (I’m fine, too.)

Person 2: Yego. (Yes.)

Oya – no. Good to say when kids bug you for money. Say it with a smile.

Sawa – OK. Sawa (pronounced sah-wah) is actually a Kiswahili word that Rwandans have borrowed and use regularly. You may hear Rwandans say “sawa,” meaning OK to something, like good morning, that you say. You may also hear them say “Ni sawa,” meaning it’s OK.

Near – hafi (pronounced hah-fee) Far – kure (pronounced kur-ay). Is it near? – Ni hafi? Is it far? – Ni kure? But, don’t always expect an accurate answer, because what’s far or near to someone else is relative.

Genda (pronounce jen-duh) – You can say this if children won’t move away from you. It’s a polite way of saying “move on” or “give me space.” If that doesn’t work, the impolite way is to say, “Hoshi” (pronounced ho-shee), which means “scram.” I have only had to say this a few times, and it works.

Woman – umugore (pronounced ooh-moo-gor-ay). Women – abagore (pronounced ah-ba-gor-ray).

Man – umugabo (pronounced ooh-moo-fah-bo). Men – abagabo (pronounced ah-bah-ga-bo).

Girl – umukobwa. Girls – abakobwa.

Boy – umuhungu. Boys – abahungu.

HELPFUL WORDS AND PHRASES FOR BUYING FOOD OR DRINK

Ufite (pronounced oo-fee-tay) means “Do you have

…?” E.g.,in a shop, you may ask the shopkeeper, “Ufite

amazi?” for “Do you have water?”

I want – Ndashaka (pronounced Da-sha-ka, as the n is barely audible) E.g. Ndashaka icupa y’amazi. I want a bottle of water.

I don’t want – There are at least 2 ways to say “I don’t want:” (1) Nabwo ndashaka. (pronounced nah-bwo da-sha-ka) or (2) Sinshaka. Example: “Nabwo ndashaka isukare” means “I don’t want sugar.”

Give me – mpa (pronounced maa). E.g. “Mpa amandazi abiri” for “Give me 2 donuts.” Note: There is not a word for please, though you can say “Mbese” (pronounced em-bess-say) to politely begin a question. When you receive your requested item, it is common to say “thank you” and the shopkeeper will say “Thank you, too.”

Napkin – serviette (pronounced sir-vee-ette-tay) is from the French word for napkin.

Icupa (pronounced EE-Chupa) is another borrowed Swahili word that means bottle. Children will be eyeing your disposable water bottles and asking for them. So, when you finish a bottle, feel free to give it to a child.

Agacupa (pronounced Ah-gah-chupa) simply means small bottle. Sometimes, children will refer to the disposable water bottles you are carrying as “agacupa.”

BEVERAGES

Water – amazi (pronounced ah-mah-zee).

A bottle of water – Icupa y’amazi. (pronounced ee-choo-pa ya-mah-zee). Usually 300 francs, but larger bottles are obviously more.

Cup – Igikombe (pronounced ee-gee-comb-bay). The plural is ibikombe.

Milk – amata (pronounced ah-mah-ta)

Black tea – mukaru – (pronounced moo-cah-roo) is sweet and spicy black tea kept hot in very large thermoses in many of the tiny shops along the Trail. It’s usually 100 francs.

Milk tea – icyayi (pronounced ee-chai). Also, called African tea. It’s also available in the small shops along the trail and is spicy and served piping hot from very large thermoses. Milk tea is the most popular hot beverage with Rwandans.

Coffee – ikawa. (pronounced ee-cow-wa). Despite Rwanda boasting excellent coffee, the coffee served in most small shops and outside the large cities is Nescafe instant coffee to which one adds hot water.

Sugar – isukare (pronounced ee-soo-kar-ay)

Juice – umutobe (oo-moo-toe-bay). A wide variety of Rwandan-made juices are available in most places. Agashya and Inyange brands are the most popular.

Fanta – generally refers to any type of soda. If you want Fanta Orange, ask for it specifically (Orange is pronounced 0r-ahn-jay). If you want Fanta Citron, ask for it specifically. There is also a tonic water soda called Kwest that is less available. Some places also have Coke (pronounced Coka in Ikinyarwanda).

Note: soft drinks and beer are usually served at room temperature. If you want yours cold, ask for “Kongye” (pronounced cone-jay). Vendors may or may not have cold beverages depending on whether they have a fridge and whether they’ve plugged it in yet today, but it’s worth it to ask.

Hot – shyushi (pronounced shoo-shee)

Cold – Kongye (pronounced cone-jay).

Beer – Inzoga (pronounced just like it’s spelled: in-zo-ga), which refers to any alcoholic beverage. Rwanda has a wide variety of beers.

FRUIT – IMBUTO

Banana – umuneke (pronounced oo-moo-ne-chay) for one banana. The plural is imineke (pronounded ee-mee-ne-chay). The bananas are mostly the small fingerling variety, and they are a quick and delicious treat while hiking the Congo Nile Trail. When you finish, give the peel to a goat.

Passionfruit – itunda. (pronounced ee-toon-dah). Plural is amatunda.

Orange –icunga (pronounced ee-choon-ga). Plural is amacunga (pronounced ah-mah-choon-ga).

Mandarin – mandarina.

Papaya – ipapayi. Plural is amapapayi.

Mango – umwembe. Plural is imyembe.

MEAT

Chicken – inkoko (pronounced in-ho-ko)

Cow – inka (pronounced inha).

Goat – ihene (pronounced ee-hen-ay).

Brochette or kebab – brochette (pronounced bro-shet-tay).

BREAD, EGGS & DAIRY

Yogurt – ikivuguto (pronounced ee-chee-voo-goo-toe) is Rwanda’s traditional liquid yogurt or kefir. Small shops keep it in large plastic containers in a fridge and serve it in a glass cup. It’s a tart and healthy drink. According to custom, one may only drink ikivuguto while sitting down. It’s usually 200 francs (about 25 cents). Some shops sell liquid yogurt in plastic containers from Rwanda’s dairy companies, but that yogurt is almost always sweetened and more expensive, and is always called “yogurt.”

Donuts – Amandazi (plural). The

singular is irindazi. These are Rwanda’s round donuts or fritters that

are sold almost everywhere. They make a

quick breakfast or snack food and travel well in a backpack. They usually cost ijana (100 francs or about

12 cents), but smaller ones can be 50 francs.

Chapati – A flat bread often sold in shops in Rwanda.

Bread – umugati (pronounced ooh-moo-ga-tee) The plural is imigati (pronounced ee-mee-ga-tee).

Honey – ubuki (pronounced oo-boo-chee). Some people like honey on bread.

Samosa – sambusa (pronounced sam-boo-sa). They are small savory meat-filled pastry pockets that make a nice lunch or snack.

Omelet – umurete (pronounced oo-moo-reh-tay).

Egg – igi (pronounced ee-jee). Plural is amagi (pronounced ah-mah-jee).

Hard-boiled eggs – amagi atetsi (pronounced ah-mah-jee ah-tet-see), which literally means cooked eggs. These are great to take on the Trail for lunch or snack, as they travel easily in a backpack.

MONEY

Money – amafaranga. The word comes from the French word “franc.” The prefix “ama” makes it plural; it’s always used in the plural.

Ijana – 100 francs or about 12 1/2 cents. (pronounced ee-jah-nah).

Igihumbi – 1,000 francs or about $8.65. (pronounced ee-gee-hoom-bee). The plural (i.e. 2000 francs and above) is “ibihumbi,” pronounced ee-bee-hoom-bee).

COUNTING

A few words about numbers. First, the easy part: the number follows the noun. Second, the more challenging part: the prefix of the number changes depending on the noun that the number modifies. For example, 3 donuts are “amandazi atatu,” but 3 men are “abagabo batatu,” 3 cups are “ibikombe bitatu” and 3 goats are “ihene eshatu.” However, if you say the basic numbers that I list below, which are the numbers used for counting without modifying a noun, everyone will understand you.

1 – rimwe (pronounced rim-way)

2 – kabiri (pronounced kah-beer-ee)

3 – gatatu (pronounced gah-tah-too)

4 – kane (pronounced kah-nay)

5 – gatanu (pronouonced gah-tah-noo)

6 – gatandatu (pronounced gah-tahn-dah-too)

7 – karindwi (pronounced kah-rin-dwee)

8 – umunane (pronounced oo-mahn-ah-nay)

9 – icyenda (pronounced ee-chee-yen-da)

10 – ichumi (pronounced ee-choo-me)

100 – ijana

Over 100 (i.e., 200 to 900) – Magana.

200 – maganabiri, which is the contraction for

magana abiri.

300 –

maganatatu

400 –

maganane

500 –

maganatanu

600 –

maganatandatu

700 –

maganarindwi

800 – magananani

900 – maganacyenda.

1,000 – igihumbi

2,000 – ibihumbi bibiri or just bibiri

3,000 – ibihumbi bitatu or just bitatu

4,000 – ibihumbi bine or just bine.

5,000 – ibihumbi bitanu or just bitanu

6,000 – ibiumbi bitandatu or just bitandatu

7,000 – ibihumbi birindwi or just birindwi

8,000 – ibihumbi umunani

9,000 – ibihumbi cyenda

Pentecostals don’t baptize until the person is older and capable of understanding the significance of baptism, capable of voluntarily choosing to be baptized and able to profess his or her faith. That idea makes sense to me, because we all inherit the religions of our parents and have no choice at birth. Instead, they have a welcoming ceremony for new babies. After the hours-long church service, we went to my colleague’s home for the official baby naming ceremony, which is a very traditional Rwandan custom that existed well before the foreign religions invaded. That ceremony was followed by a feast of food.

Pentecostals don’t baptize until the person is older and capable of understanding the significance of baptism, capable of voluntarily choosing to be baptized and able to profess his or her faith. That idea makes sense to me, because we all inherit the religions of our parents and have no choice at birth. Instead, they have a welcoming ceremony for new babies. After the hours-long church service, we went to my colleague’s home for the official baby naming ceremony, which is a very traditional Rwandan custom that existed well before the foreign religions invaded. That ceremony was followed by a feast of food.

And, bicycling in Rwanda is hard work. Rwanda is HILLY. Unlike Buck’s County, Pennsylvania’s rolling ridges, Rwandan hills are everywhere and in no order. The uphills are a strenuous workout, and the downhills are exhilarating and even harrowing – especially when there is a speed bump strategically placed at the bottom of a hill.

And, bicycling in Rwanda is hard work. Rwanda is HILLY. Unlike Buck’s County, Pennsylvania’s rolling ridges, Rwandan hills are everywhere and in no order. The uphills are a strenuous workout, and the downhills are exhilarating and even harrowing – especially when there is a speed bump strategically placed at the bottom of a hill.

And, they ride up and down on steep dirt trails in and around town.

And, they ride up and down on steep dirt trails in and around town.

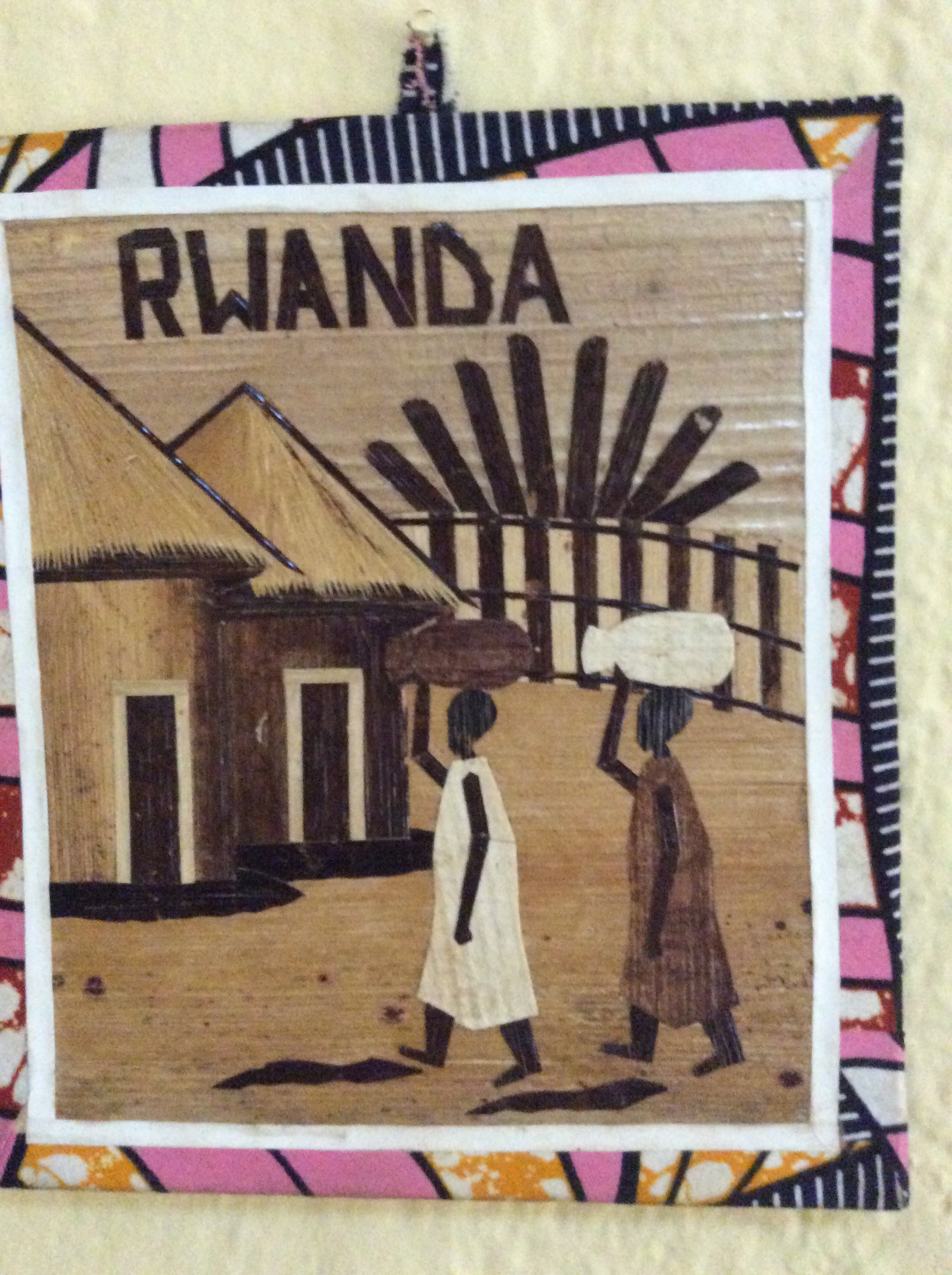

Below is a small wall hanging made of pieces of wood pasted onto fabric-covered cardboard. It depicts the traditional cozy Rwandan huts protected by an enclosure at the time the first Europeans arrived in Rwanda in 1894. Like most Africans, Rwandans have amazing posture and are adept at carrying many things on their heads.

Below is a small wall hanging made of pieces of wood pasted onto fabric-covered cardboard. It depicts the traditional cozy Rwandan huts protected by an enclosure at the time the first Europeans arrived in Rwanda in 1894. Like most Africans, Rwandans have amazing posture and are adept at carrying many things on their heads.

We came upon a tea plantation, where the harvesting and collection of the tea leaves was in process. Rwanda is known for its black and green tea. The workers invited us to have a look at their harvest.

We came upon a tea plantation, where the harvesting and collection of the tea leaves was in process. Rwanda is known for its black and green tea. The workers invited us to have a look at their harvest.

While we waited for our bus, Béné called Mary of RDB to complain about Benoit’s bad advice and the “Hotel California-ish” experience we had had in Busenge. Béné believed that the inn was a house of prostitution, while I thought that perhaps it was simply a convenient place for a quick afternoon tryst. Mary assured us that it was not RDB’s intent to direct hikers to such a place.

While we waited for our bus, Béné called Mary of RDB to complain about Benoit’s bad advice and the “Hotel California-ish” experience we had had in Busenge. Béné believed that the inn was a house of prostitution, while I thought that perhaps it was simply a convenient place for a quick afternoon tryst. Mary assured us that it was not RDB’s intent to direct hikers to such a place.

Not only were the rooms spotlessly clean and neat and the grounds perfectly manicured, it was situated on a cliff overlooking Lake Kivu with fabulous views of the lake and the Democratic Republic of Congo on the far side of the lake. We were treated to an exquisite sunset over the Congo side of the lake.

Not only were the rooms spotlessly clean and neat and the grounds perfectly manicured, it was situated on a cliff overlooking Lake Kivu with fabulous views of the lake and the Democratic Republic of Congo on the far side of the lake. We were treated to an exquisite sunset over the Congo side of the lake.

I had a wrap made out of chapatis. The next morning, our scrumptious buffet breakfast of mushroom soup, waffles, hard boiled eggs, bread, margarine, jam honey and an array of fruit (mango, papaya, pineapple), as well as coffee, tea, African tea or hot milk to drink was included in our 15,000 franc (less than $17) room rate.

I had a wrap made out of chapatis. The next morning, our scrumptious buffet breakfast of mushroom soup, waffles, hard boiled eggs, bread, margarine, jam honey and an array of fruit (mango, papaya, pineapple), as well as coffee, tea, African tea or hot milk to drink was included in our 15,000 franc (less than $17) room rate.