This was my third trip with students to Mpanga (pronounced Mhanga) Prison. On my first trip, I was eager to visit a prison in another country and compare it to ours. In the late 1970s, when I was a law student, I worked for an office that provided legal assistance to prisoners and, as a result, regularly visited Illinois prisons. Each prison visit was physically and mentally grueling, the prison conditions were depressing, the inmates were cheerless and desperate to talk to us, and the administration was openly hostile to the prisoners and us. Mpanga Prison is nothing like that. So, after my first trip, I happily returned for a second and third trip because Mpanga Prison is an exceptional and most interesting prison. Its staff are cordial, professional and proud of their work. The prisoners, despite most being in severely overcrowded conditions, appear to be at ease. Almost all smiled as they greeted and welcomed us.

Mpanga Prison is a half hour drive from Nyanza, the town I live and work in. It’s at the end of a hilly and dusty dirt road that winds through stunningly beautiful scenery of endless rolling hills studded with trees.

In between the hills are green valleys covered with banana plantations and small family farms. In every direction, the land is dotted with compact stucco and mud-brick homes with tin or terracotta roofs.

Suddenly, our bus of law students is at the main prison gate, where a guard, expecting us, allows our bus into the prison compound. We park near the entrance, in front of a communal area where guests are received. It is across from the infirmary, which we would soon learn is staffed by eight nurses, with at least one nurse on duty at all times. We were also informed that prisoners with serious health problems are taken to the Nyanza hospital.

It is an easy walk to a room that had been converted into a small auditorium for us to watch a PowerPoint presentation by the serious but congenial Prison Director who speaks with obvious pride about the prison and its prisoners.

Mpanga Prison opened in 2005 and has a population of 7,072 men. It is a hybrid prison housing domestic and international prisoners. The domestic prisoners are housed in three wings or areas: Golf Wing is the largest with 5,563 men, followed by Juliet Wing with 818 men, and then Romeo Wing with 676 men. Compared to the domestic prisoners, the international prison population housed in Delta Wing is tiny, consisting of only 15 men.

What makes a prisoner an international prisoner and entitled to be placed in the comparatively cushy international wing is not his nationality but the place he was arrested. Thus, a Rwandan arrested in Rwanda for genocide crimes is housed in the general population, while a Rwandan who escaped across the border to neighboring Congo or elsewhere in the world after the Genocide is housed in the international wing. Where a prisoner is housed makes an enormous difference, as the United Nations requires high standards for international prisoners. For instance, international prisoners are entitled to much better food, much larger and more private living space, much nicer living quarters and conjugal visits.

There are two kinds of international prisoners at Mpanga Prison. The first are accused or convicted genocidaires. “Genocidaire” is the French word for those who fomented or participated in the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. After the Genocide, the United Nations created the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), in Arusha, Tanzania. The ICTR convicted 61 individuals, most of whom were imprisoned in countries other than Rwanda. The ICTR officially closed in 2015 but, before closing, transferred its remaining (or residual) work to the UN’s International Residual Mechanism for Rwanda, which is also located in Arusha Tanzania. As a result of judicial reforms in Rwanda, including abolition of the death penalty and establishment of a special high court chamber to try suspected genocidaires, some accused genocidaires have been extradited to Rwanda to stand trial. However, the process has been slow. Since 2012, although Rwanda has sought to arrest about a thousand suspected genocidaires living aboard, only about 19 suspected genocidaires arrested outside of Rwanda have been extradited to Rwanda for trial. Twenty-five years after the genocide, many suspected genocidaires remain at liberty abroad, mostly in countries without extradition treaties with Rwanda.

The second kind of international prisoners at Mpanga Prison come from the West African country of Sierra Leone. In 2009, eight prisoners convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity by the UN Special Court for Sierra Leone were housed at Mpanga Prison because there were no prisons in Sierra Leone that met the UN’s standards. Those prisoners were convicted of war crimes (including mutilation of civilians, sexual slavery and conscripting children as soldiers) committed during Sierra Leone’s more than decade-long civil war (1991-2002). Currently, five Sierra Leoneans remain at Mpanga Prison.

We were allowed to mingle and talk with the international prisoners who chose to talk to us. It was hard to reconcile in our minds that the men who graciously invited us into their rooms to look around, who pointed to photos on their walls of their families and whose hands we shook had committed such crimes. When some of us remarked at the differences between the international wing and the other wings, the men reminded us that it was still prison.

After exploring the international wing, we were taken to Golf Wing, where the largest group of prisoners (5,563) is housed. Golf Wing is quite crowded with bed after bed after bed after bed with little space in between, but surprisingly neat. On an earlier trip, we observed prisoners doing group exercises in military fashion in the large prison yard adjacent to their dormitories. On my latest trip, we saw prisoners playing checkers (an extremely popular pastime in Rwanda) and watching a soccer game on TV. But most were gathered in huge crowds watching us, waving and smiling at us. Everyone smiled and responded when we waved or greeted them. As we left, we shook the hands of so many of the men.

As we walked around the prison grounds, we saw several guards, both male and female. They conversed with us and the prisoners in a friendly and respectful way, as if there was no difference between them and the prisoners.

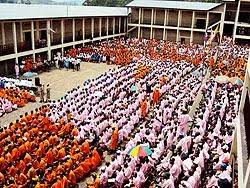

All prisoners wear simple prison garb (matching boxy cotton shirt and pants). However, the convicted prisoners are distinguished from those not yet finally convicted by the color of their garments: bright orange for the convicts and pastel pink for those not finally convicted. I use the phrase “not finally convicted” because Rwanda’s legal system follows Civil Law (think French law, which was inherited by French and Belgian colonies of the world, like Rwanda) as opposed to Common Law (the British system, which was inherited by British colonies, like the USA). In the Civil Law legal system, a defendant may obtain a second trial on appeal and the court proceedings are not considered final until the time for all appeals has lapsed without further appeal or the last appeal has concluded. If a case is on appeal, the defendant is not yet considered convicted. Because we were not allowed to take photos of the prisoners, I’ve included this photo of Golf Wing that I found on the internet.

Because Mpanga is an international prison, UN inspectors regularly inspect it to ensure that it continues to meet UN standards. Also, because it has a certain degree of notoriety as a result of being an international prison, it attracts many visitors, including us. When a group like us visits the prison, prisoners are permitted to set up a craft fair to sell us items they made. Those prisoners make the most of their time by transforming basic and discarded materials into beautiful handicrafts to sell to visitors.

On my first visit to the prison, some talented prisoners performed Rwanda’s legendary Intore dancing for us. Traditionally, Intore dancers were the king’s warriors, who were trained both as warriors and dancers – not unlike Native American war dancers. Mixing dance and war is a clever combination, which unfortunately has not been adopted by modern armies. The Intore dancers wear headgear made from a special tree to resemble a lion’s mane. Their dancing conveys the raw hyper-masculine electric energy of an ancient warrior. Because we weren’t allowed to take photos in the prison, I’ve included a YouTube video of Intore dancers so that you can see how exciting they are.

At Mpanga Prison, the prisoners perform all of the work. They cook the food. They tend the grounds, which are quite beautiful with lots of blooming flowers. In the U.S., one would not expect to see flowers and meticulously landscaped grounds in a prison; yet, at Mpanga Prison, they are commonplace and make the prison grounds feel less prison-like and actually park-like. The prisoners do voluntary work in the many acres of farm fields surrounding the prison to produce food for the prisoners and prison staff. They have banana and coffee plantations, as well as numerous vegetable gardens. The prisoners enjoy going outside the prison to work in the gardens and plantations; not only is it nice to go out beyond the prison walls, but they can eat a few extra bananas or avocadoes while working. And, they raise cattle and pigs. As we walked around the prison compound, a flock of turkeys was always near, with the big tom turkey even displaying his feathers – for either us or one of the female turkeys.

Sometimes, prisoners are taken to work in places far outside the prison. For instance, they often come to Nyanza to cut down trees for various reasons. The town of Nyanza used prisoners to cut down the trees where the bats had taken up residence, including the trees around my house. Prisoners also cut down the many tall trees that were in the way of construction of our new school building. Not only does such work improve the prisoners’ self-esteem and contribute to the running of the prison, it prepares the prisoners for eventual re-entry into the larger society.

On our drive back to the institute, we were treated to the beginning of a beautiful sunset. Because Rwanda is only 138 miles south of the equator, every day of the year is of the same length (give or take a minute or two). So, sunrise is at 6:00 a.m. and sunset is at 6:00 p.m. every day, like clockwork.

Why can’t we have prisons like Rwanda and some other the Scandinavian Countries instead of treating people like animals?

The items the prisoners made are beautiful.

Thanks for sharing Pat

LikeLike

Pat, very enlightening. Seems somewhat unsafe to have prisoners doing work in the unprisoned population.

As always, the integrity of your writing, exquisite details, subject matter and historical knowledge make this rumination extra special!! Will re-read several more times.

Going to get some shut-eye. Much 💕

Shelly

>

LikeLike

I find this article really interesting. Having seen those guys out in the fields, I marvel that they do not escape more often. I think there is something inherently “obedient” about those who’ve been caught and imprisoned in Rwanda… or maybe it’s this prison in particular that encourages inmates to stick it out.

LikeLike